You might assume I know something about teaching kids to read. I studied English at UCLA and obtained my master’s in education at The City College of NY. I taught special education grades 5-8 for 7 years, and I’ve supported schools and teachers throughout the Bronx with K-8 ELA instruction over the past 3 years.

Yet you’d be wrong. I’ve come to realize I know next to nothing.

In case you haven’t been aware, there’s been a firestorm of educators on platforms like Twitter gaining newfound awareness of the science of reading, with an urgent bellows inflamed by the ace reporting of Emily Hanford. For a great background on this movement, with links, refer to this post by Karen Vaites. And make sure you check out Hanford’s most recent podcast (as of today!!! It’s amazing!) outlining how current classroom practice is misaligned to research.

Impelled by this burgeoning national and international conversation, I’ve sought to educate myself about the science of reading. I began with Mark Seidenberg’s Language at the Speed of Sight, took a linguistics course, and have just completed David Kilpatrick’s Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties. Seidenberg is not only pithy, but furthermore impassioned, while Kilpatrick is deeply versed in both the research and application in practice as a former school psychologist. Both experts provide an incendiary takedown of more than a few sacred cows in the educational establishment.

It’s been fascinating to learn more about the science of reading while simultaneously working with a school where I could see problems elucidated by reading researchers and advocates play out in real-time. It has made what I’m learning gain an even greater sense of urgency. I would read pages critiquing the “three-cueing system” and balanced literacy approaches on the bus in the morning, then walk into classrooms where I saw teachers instructing students, when uncertain about a word, to use guessing strategies such as “look at the picture” and the “first letter of the word,” rather than stress the need to be able to decode the entire word (for more on the problems with current classroom practice, listen to Hanford’s podcast).

There’s so much to digest and apply from all of this. This post is my attempt to begin synthesizing the information I’ve read. I’ll start general and then focus on the word-level reading aspect of the research in this post. And there’s so much more I want to cover, but I’ll be leaving tons of stuff out that I would love to explore further. Someday . . .

Reading Can Be Simple

First off, though reading is complicated, it can be outlined by a simple model, known aptly enough as The Simple View of Reading. It can even be put into the form of an equation. The theory was first developed in 1986 by researchers Gough and Tunmer. The original formulation was D (decoding) X LC (linguistic or language comprehension) = Reading Comprehension.

After years of further research, this distinction has mostly held up, though it has become greatly expanded, especially in our understanding of what constitutes language comprehension.

Decoding has been clarified as one umbrella aspect of word-level reading, which is composed of many sub-skills. A more updated formula, courtesy of Kilpatrick, is:

Word Recognition X Language Comprehension = Reading Comprehension.

If you struggle with word recognition (such as with dyslexia), or if you struggle with language comprehension (English language learner), then you have difficulty reading.

Protip: if you are an educator in NY, know that this distinction can be framed around the language from Advanced Literacy as code-based (word recognition) and meaning-based (language comprehension) skills. And if you are a NYC educator, you can furthermore align this to the Instructional Leadership Framework. Bonus points for alignment to state and city initiatives! Yay!

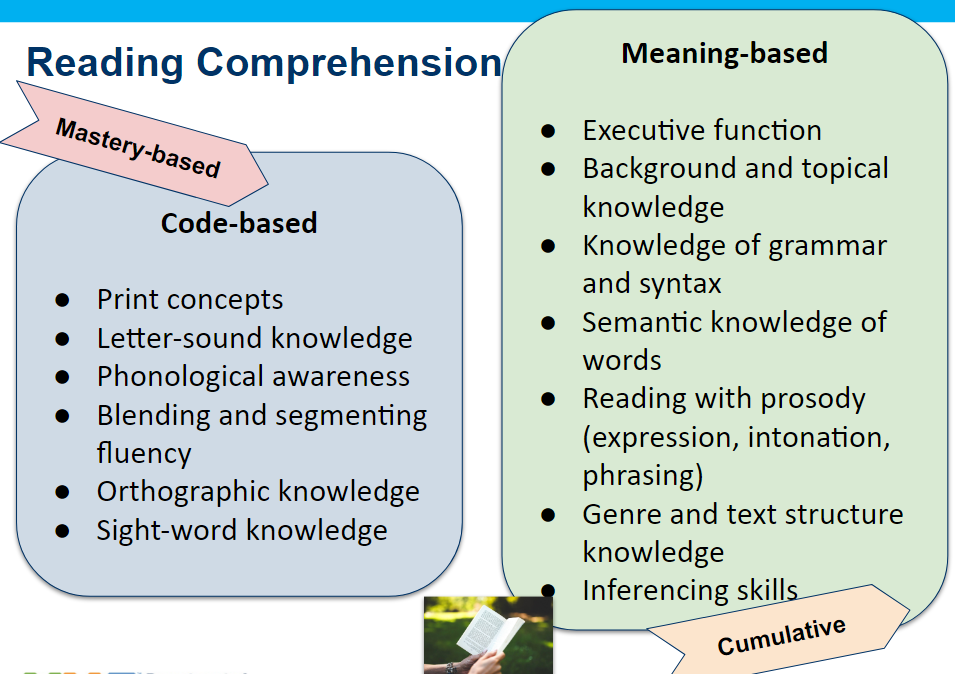

Within each of these two domains lie the various sub-skills and knowledge that make reading so very complicated. Here’s a chart I made to visualize the “Expanded” Simple View:

Protip: Most educators are already familiar with the “five pillars” or “Big 5” of reading instruction: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension, so it can be helpful to build a bridge between that knowledge and the Simple View. At a recent session I facilitated, I asked teachers to consider the Big 5, introduced the notion that they are composed of subskills, then asked them to sort those subskills into code-based or meaning-based groups. Here’s a print-out you could use to create the sorting strips.

Note that word recognition skills are mostly mastery-based. And a key point experts like Seidenberg and Kilpatrick make about word recognition is that word recognition can be acquired by all children. IQ discrepancy is not a factor.

Here’s Seidenberg:

“For children who are poor readers, IQ is not a strong predictor of intervention responses or longer-term outcomes. Moreover, the behavioral characteristics of poor readers are very similar across a wide IQ range. . . Within this broad range of IQs, poor readers struggle in the same ways, need help in the same areas, and respond similarly to interventions. In short, the skills that pose difficulties for children are not closely related to the skills that IQ tests measure. The primary question is about children’s reading—whether it is below age-expected levels—not their intelligence.”

Here’s Kilpatrick:

“Discrepancies between IQ and achievement do not cause word-reading problems. Rather, deficits in the skills that underlie word-level reading cause those problems. The component skills of word reading can be strong or weak, independently of IQ test performance.”

“A common belief that continues to be recommended is that some students with severe reading disabilities simply cannot learn phonics and they should be shifted to a whole-word type of approach. This recommendation is inconsistent with the accumulated research on the nature of reading development and reading disabilities

“The simple view of reading applies to poor readers with IDEA disabilities (SLD, SLI, ID, ED/BD, TBI) and poor readers not considered disabled. Thus, when asked the question, ‘Why is this child struggling in reading?’ we would no longer answer, ‘because the child has an intellectual disability (or SLI or ED/BD or whatever).’ Those disability categories do not cause reading difficulties—specific reading-related skill deficits cause reading difficulties.”

What this means for educators: there is simply no excuse for any student to graduate from any of our schools without the ability to decode words in print. As Kilpatrick stated in a presentation (thanks to Tania James for her wonderful notes), “If a child can speak, they can learn phonics.”

Language comprehension, on the other hand, may be a tougher beast to tackle. Linguistic skills and knowledge are cumulative and on-going. Most importantly, a core component of language comprehension is background and topical knowledge, in addition to grammatical and syntactical knowledge — both which are inadequately taught in most schools due to the lack of a strong and coherent core curriculum.

I should note that Siedenberg doesn’t seem to fully subscribe to the Simple View, and that by no means should we begin to think any one model can adequately describe something so complex as reading. In his endnotes he states, “The main weakness in Gough’s theory is that it did not make sufficient room for the ways that the components influence each other. Vocabulary, for example, is jointly determined by spoken language and reading. Vocabulary can also be considered a component of both basic skills and comprehension.”

Kilpatrick contradicts this view when he states, “In the context of the simple view of reading, it appears that vocabulary belongs primarily on the language comprehension side of the simple view equation, not necessarily on the word-reading side.”

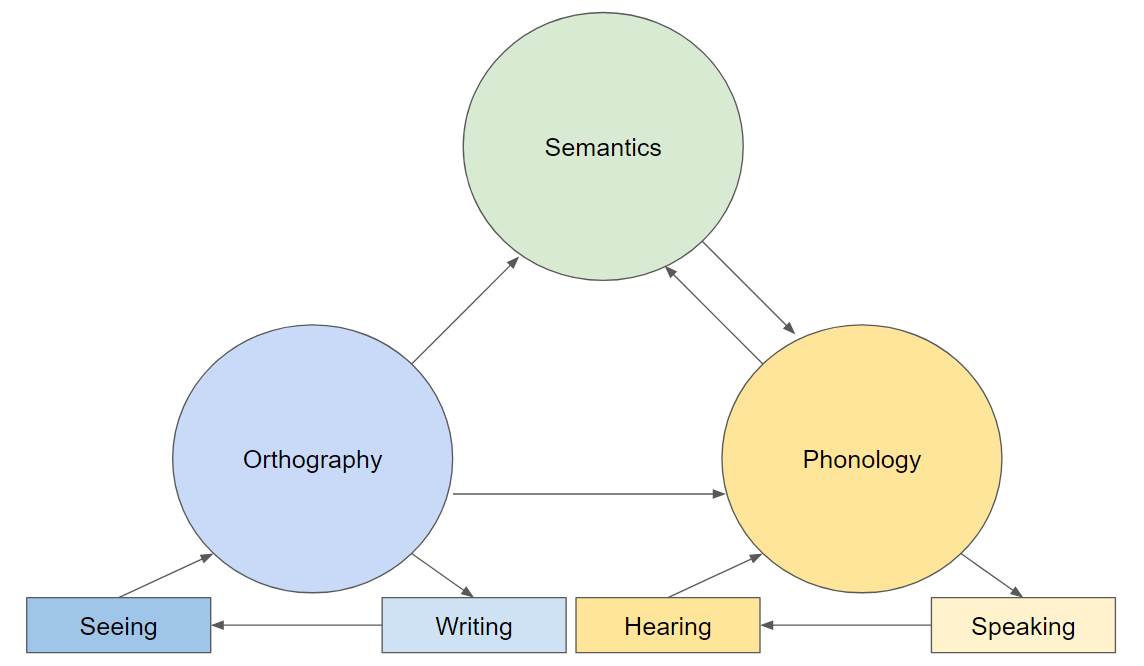

Seidenberg proposes his own model, based on computational simulations, which looks something like this (Figure 6.2 from Chapter 6):

I think this model is useful for conveying why reading is complicated and can be hard to learn, but maybe not quite as useful for guiding school-based assessment and instruction.

Why is The Simple View of Reading important?

Having a clear model for reading comprehension means we have a guide for aligned assessment, prevention, and intervention. Unfortunately, many schools base ELA instruction primarily on state assessments, which tell you very little about a student’s reading needs. People seem to forget that the function of a state assessment is for school, district, and state level accountability, not to direct classroom instruction.

Protip: One “research snapshot” I found useful from Nonie Lesaux and Emily Galloway’s Advanced Literacy framework is the distinction they make between “literacy performances” and “specific skills and competencies.”

A state literacy assessment is a “literacy performance.” Here’s an explanation in their book, Teaching Advanced Literacy Skills:

“There is a tendency to examine the results of outcome assessments at the item level—to figure out the types of items groups of students struggled with and then go back and teach to support this understanding. Perhaps the most universal example is ‘finding the main idea’ in a passage . . . the problem is that finding the main idea—among many other similar performances or exercises—is just that—a reading performance. It is not a specific skill. That is, to perform the task at hand, in this case to find the main idea, the reader draws on many component skills and composite competencies and initiates those in concert with one another. In turn, when a student is not able to find the main idea, we still do not know why.”

In order to know why, we need assessments that can better pinpoint where the breakdown occurs, whether in word recognition or in language comprehension, or both. And then we need to do something about it. This is where it gets hard.

Reading is Hard

Though we can draw on a simple model to explain it, in actuality reading is complicated.

First of all, it’s completely unnatural. While we acquire spoken language organically, reading requires the imposition of an abstract system onto that language, a grafting of a fragmented alphabet onto a river of sound. Writing is something our species invented, an ingenious mechanism to convey information across space and time. While the first writing appeared around 3,200 BC, humans have been speaking for anywhere between 50,000 to 2 million years prior (we don’t know for sure because we couldn’t record anything yet, duh).

There are many irregular words in the English language, which would appear to make the teaching of something like phonics a daunting endeavor. We assume that kids need to be taught the rules, and then memorize the exceptions (these are known as “sight words.”) Makes sense, right?

Yet research has made it clear we don’t acquire most sight words through memorization. Instead, we draw upon our letter-sound knowledge and phonological analysis skills to recognize new written words and unconsciously add them to our “orthographic lexicon.”

What’s interesting on this point is there appears to be some disagreement between the models Seidenberg and Kilpatrick use to explain this process. Seidenberg calls it statistical learning, meaning that we learn to recognize patterns in common words, from which we then can recognize many others, including ones with irregularities. Kilpatrick, on the other hand, terms it orthographic mapping, which is the process of instantaneously pulling apart and putting back together the sounds in words, drawing upon letter-sound knowledge and phonemic awareness. In either model, what is acknowledged is that children learn to recognize a large volume of new words primarily on their own, but that such an ability is founded upon a strong understanding of sounds (phonology) and their correspondences in written form (orthography).

Honestly, I find both concepts—statistical learning and orthographic mapping—hard to wrap my head around.

It’s also possible they describe different things. Seidenberg’s term seems more global, explaining how we acquire vocabulary, while orthographic mapping refers more specifically to the relationship between decoding and acquiring vocabulary. I should note here that Kilpatrick did not come up with the term, “orthographic mapping,” but rather draws on the research of Linnea Ehri.

Here’s Seidenberg on statistical learning:

“…learning vocabulary is a Big Data problem solved with a small amount of timely instruction and a lot of statistical learning. The beauty part is that statistical learning incorporates a mechanism for expanding vocabulary without explicit instruction or deliberate practice. The mechanism relies on the fact that words that are similar in meaning tend to occur in similar linguistic environments.”

Here’s Kilpatrick on orthographic mapping:

“Roughly speaking, think of phonic decoding as going from text to brain and orthographic mapping as going from brain to text. This is, however, an oversimplification because orthographic mapping involves an interactive back and forth between the letters and sounds. However, it is important that we do not confuse orthographic mapping with phonic decoding. They use some of the same raw materials (i.e., letter-sound knowledge and phonological long-term memory), but they use different aspects of phonological awareness, and the actual process is different. Phonic decoding uses phonological blending, which goes from “part to whole” (i.e., phonemes to words) while orthographic mapping requires the efficient use of phonological awareness/analysis, which goes from “whole to part” (i.e., oral words to their constituent phonemes).”

Kilpatrick notes that “The vast majority of exception words have only a single irregular letter-sound relationship.” This means that if a reader knows their letter-sound relationships well, they will be able to negotiate the majority of words with exceptions and irregularities.

What this means is that students need to be provided with sufficient practice to master phonological awareness and phonics skills. And we can not blame the failure of a student to learn to decode on the irregularity of the English language.

Phonology: What We Can Hear and Speak is the Root of Written Language

In Seidenberg’s book, he argues that phonemes are the first abstraction on the road to the written word. A phoneme is the individual sound that a letter can represent (e.g. the sound of “p”). While we learn many such sounds as we acquire spoken language, the need to disaggregate a single component sound into a phoneme only becomes necessary in the translation of speech into the written form. As Seidenberg puts it:

“Phonemes are abstractions because they are discrete, whereas the speech signal is continuous. . . The invaluable illusion that speech consists of phonemes is only completed with further exposure to print, often starting with learning to spell and write one’s name.”

No wonder “phonemic awareness” is central to learning to read! The ability to know and discern individual sounds, and then to be able to play with them and put them back together, is the core skill of reading. In other words, if you struggle with blending and manipulating the sounds in words, you struggle with reading.

And indeed, this is why far too many of our kids have problems with reading. As Kilpatrick puts it, “The phonological-core deficit is far and away the most common reason why children struggle in word-level reading.”

Once I grasped this deceptively simple idea—that fluent reading is dependent on the ability to hear and speak the sounds of letters within words—prevention and intervention began to make more sense to me. Before, my understanding of the distinction between phonological awareness and phonics and what this meant for instruction was muddy. Now, I know that before even looking at a letter or a word, a student needs to practice hearing and speaking the sounds. This is how the student develops phonemic awareness. Phonics, on the other hand, is taught when those sounds are then applied to letters.

Protip: “A good way to remember the difference…is that phonemic awareness can be done with your eyes closed, while phonics cannot” (Kilpatrick, 2015a, p. 15).

The Importance of Advanced Phonemic Awareness

That may sound straightforward (no pun intended), but one of the key understandings I gained from Kilpatrick is that we too often stop at basic phonological awareness, both in our assessments and in our intervention. While sound instruction in grades K-1 in phonological awareness and phonics should help to prevent most word reading difficulties (“Intervention researchers estimate that if the best prevention and intervention approaches were widely used, the percentage of elementary school students reading below a basic level would be about 5% rather than the current 30% to 34%”), there are some students who will present with more severe difficulties. And those difficulties often stem from lacking more advanced phonemic awareness. He also points out that these advanced phonemic skills continue to typically develop in grades 3 and 4, well past the point that most schools provide systematic phonemic and phonics instruction.

Kilpatrick stresses that intervention and remediation for such students requires explicitly teaching advanced phonological skills.

So What Can We Do?

The great thing about Kilpatrick’s book—and why you should buy it—is that unlike many writers in the field of education, he actually goes through what assessments you can use and what you can do instructionally, both for prevention (K-1) and for intervention (grades 2 and up), to address reading needs. He calls out programs by name and praises or critiques them based on key understandings from the research, and some of it was pretty surprising to me.

But I’m going to stop here for this post before it gets overlong. When I can find time to post again (it’s seriously hard with a 2 year old and 9 month old and the school year is about to begin), I’ll share some of the assessments and programs that I think are most accessible from Kilpatrick, as well as dig into some of the sacred cows that Kilpatrick, Seidenberg, and Hanford have slayed.

Afterword

You’ll notice I didn’t mention what I learned from my linguistics course, which was just an online series. It was fine, but I only found it useful insofar as it equipped me with some terms like lexicon, morphology, semantics, or pragmatics. If you have any recommendations for further learning in linguistics, please let me know.

Also, if I’ve demonstrated any misconceptions in this piece or you would like to challenge or add to anything I wrote, please share!

And thank you for reading.

Good for you for making the effort to learn and share all of this. I also,on the advice from Mark Seidenberg, took (still taking) a linguistics course. The free mooc from the virtual linguistics campus Univ of Marlberg provides an in-depth overview. It really delves into phonology which I have found to be valuable as a reading teacher.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Sarah. You know it’s funny, I just looked up the Virtual Linguistics Campus and realized I’d signed up at some point, and must have dropped it in the midst of other things. It looks like there are some useful videos in there on grammar as well!

LikeLike

I get it. At some point I had started the mooc on Coursera but had to drop it. The VLC course is different and more detailed in some ways. I suggest reading Linguistics for Dummies for a good overview.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well said! Thank you so very much for your generous sharing of your learning . So many connections come to mind as I read your insights. You are reminding us of the importance of prioritizing time in the classroom to explicitly these essential reading skills and give students time to practice them while reading. I look forward to your next post! Best wishes for the school year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading and for sharing! Best wishes to you as well.

LikeLike

Thank you for a great blog post! I appreciate how you discussed the Simple View of Reading, and added the terminology of Code-Based (Mastery-Based) and Mastery-Based. I think the Simple View of Reading Are and Scarborough’s Rope infographic are critical to helping educators understand the complexity of learning to read and move beyond their current teaching theories and practices and that the reading science community is not just pushing phonics.

I thought it was interesting that you viewed Mark Seidenberg’s statistical learning and David Kilpatrick’s orthographic mapping as a disagreement. I understood them as complementary explanations of the same process – that the the statistical learning explains how the reader learns which representation of the sounds is the correct one (and the one to map when their are multiple possibilities). Their knowledge of the code and morphology, helps them narrow the choices; statistical learning helps them learn the right one; and advanced phonemic awareness (to the level of automatic manipulation) is required to make it work.

LikeLike

Rachel, thank you for your comment and for your pushback on statistical learning vs. orthographic mapping. I think you are right that they complement one another, rather than operate in direct disagreement. I think what I was struggling with as I looked across my notes from the two authors was that they have applied different terms to similar processes. I also picked up on some critique coming from Kilpatrick of statistical learning when I reviewed Tania James’ notes from his presentation in LD Australia (http://bit.ly/drKilLDA) and noticed that he mentions statistical learning there. I just went back and reviewed it again, and now I noticed he seems to be saying that it’s a related process, though not as efficient as orthographic mapping, in that it requires more exposures. Seems like this is an area where more research is needed, or at the very least, some broader consensus on specific processes and terms.

LikeLike

You might enjoy https://linguisteducatorexchange.com

LikeLike

Pingback: Learning how kids learn to read | DECODING DYSLEXIA WISCONSIN

A very well written piece that I appreciate very much as a reading teacher. Thank you. Keep the articles coming.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So helpful! Thank you very much for working this all out. It’s amazing that you’ve articulated it so well by starting with knowing “next to nothing.” Again, thank you. I shared this with my audience.

I hadn’t noticed the absence of discussion about orthographic mapping in Seidenberg’s book. Good point! He only has one reference from Ehri, who’s the main theorist and researcher in that domain. Kilpatrick refers to her extensively, however, and is helping the field by bringing her research to the forefront. He says it’s hard to understand so he thinks a lot of researchers haven’t read her in depth. She’s prolific!

Like Rachel Hurd in the comments, I too, see statistical learning and orthographic learning as interrelated. As Seidenberg writes,

“Readers become orthographic experts by absorbing a lot of data, which is one reason why the sheer amount and variety of texts that children read is important. For a beginning reader, every word is a unique pattern. Major statistical patterns emerge as the child encounters a larger sample of words, and later, finer-grained dependencies such as the fact that syllables can both begin and end with ST, begin but not end with TR, end but not begin with BS, and SB can only occur across syllables (e.g., DISBAR). The path to orthographic expertise begins with practice practice practice but leads to more more more….We don’t study orthographic patterns in order to be able to read; we gain orthographic expertise by reading” p. 92.

In the above paragraph, Seidenberg is glossing over the incredible process of orthographic mapping that Kilpatrick goes deep into. Both are adding a helpful perspective. As the reader attacks an unknown word, she subconsciously relies on her statistical-learning brain, to play around with the unknown sounds in word to transform a partial, inaccurate decoding into an accurate decoding.

At that juncture, she has the possibility of orthographically mapping the specific sequence of letters to the sounds in the words–storing the word as a unit in her long-term memory. So statistical learning is part of the process that leads to the ability to orthographically map the new word. Relatedly, her orthographic learning bank, so to speak, is what she draws on–in addition to phonology and semantics–in the statistical learning process.

Kilpatrick is on the vanguard of getting the concept of “orthographic mapping” out into the teachers’ domain so there’s still a lot we have to learn!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Marnie, thank you so much for your in depth and thoughtful response! This is so helpful for clarifying the two, which you could see I was struggling with connecting. This makes sense. I’m going to use your explanation as my anchor from hereon! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Manderson, there are some points you have mentioned which I may be able to help with. Please, let us discuss.

LikeLike

Pingback: Applying What I’m Learning About How Kids Learn to Read – Schools & Ecosystems

Pingback: The Magic of the Rime: Mapping Sounds to Letters – Schools & Ecosystems

I wonder if differently wired brains (whether different innately or b/c of different instruction and practice) might approach the same task differently, so that the “statistical” vs. the “orthographic” happen to different varying degrees for different people.

LikeLike

Thanks – nice job. I hope you are coming to Everyone Reading on Feb 3rd and 4th at the CUNY grad center, and bringing lots of friends! My blogs are on the Education Post Website. I’ll be giving a presentation on dyslexia at CEC4 on January 8th and am happy to repeat it for any NYC school, pta, CEC, etc.

LikeLike

Hi Debbie! We met afterwards very briefly at ResearchEd in Philly! Thanks for forwarding the Everyone Reading event (here for readers if you’re interested: https://www.eiseverywhere.com/ehome/473134). I’ll see if I can arrange attendance for this. Any idea if we can arrange something specific for a group of NYCDOE admins?

LikeLike

Thank you for allowing my comment.

You wrote, “A common belief that continues to be recommended is that some students with severe reading disabilities simply cannot learn phonics and they should be shifted to a whole-word type of approach. This recommendation is inconsistent with the accumulated research on the nature of reading development and reading disabilities”.

About 20% of children shut down from learning when things are confusing to them. Many teachers around the world teach phonics wrongly. This is the basic reason why many kids are unable to read and end up in intervention classes.

A logical thinking kid simply cannot see how ‘buh air luh luh’ can be ball.

Neither can he figure out why cuh air tuh can result in cat.

He shuts off from learning and then is classified as dyslexic and unable to learn using phonics.

Believe me, this problem is going to get worse as the episode ‘Charlies Alphabets’ under Baby TV creeps into more living rooms.

Please read part one of my email to the producers of Baby TV. Do listen to the sounds of the letters pronounced in the video clip.

https://www.dyslexiafriend.com/2018/10/correspondence-to-and-from-babytv-and.html

Please grill me with any question you may have and I will respond.

LikeLike

Thank you. Your blog was very informative as I’m toying with whether to buy the book.

I’m live the U.K.

phonics is taught in school to children aged 4 and up. When a child is aged 5/6 ( year 1) depending on their birthday a statutory on line phonics test is given to all children in primary school. This takes place every June.

This is a government directive and takes place across all of the U.K in all state schools.

This isn’t the case in private fee paying schools. They administer different tests and checks.

The National pass marks is 32 out of a possible 40 real words and nonsense words.

I’m a SEN tutor so I often tutor children with other challenges that often go hand in hand with an eventual diagnosis of Dyslexia.

I currently tutor 11 children with reading challenges some whom have been diagnosed with Dyslexia.

Very few schools in the uk have trained specialist teachers in schools so often children difficulties are picked up invariably late on.

This can be for numerous reasons. Sadly I’m often having to pick of the pieces. Well it’s a team effort home, school and tutoring. Not forgotten the hardworking pupil.

I’m interested to read more.

I will follow your blog.

LikeLike

Thanks for reading and sharing, Sara! I highly recommend the book by Kilpatrick (Essentials), it really lays out the components of reading and assessments that go with them in a comprehensive way that will support your work.

LikeLike

I too would recommend the book by Dr. David Kilpatrick. I have read that book from cover to cover a number of times. In fact, you will see my name on the acknowledgment page.

As you are working with ‘dyslexic’ kids, I would also recommend you to read my articles on how I have taught more than 70 such kids. You may find it useful.

Google my name and you will be able to assess my articles in my blog.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Literacy & Language and commented:

I’ll be reblogging some older posts from Schools & Ecosystems here that really make more sense as anchors for this blog. This is the one that will center much of what Literacy and Language Blog will be all about!

LikeLike

Pingback: The Trouble With Common Word Recognition Strategies – eduvaites